During my leave over the summer I was really glad to catch the performance Arctic Requiem outside the Shell Centre in August. Here’s a piece I wrote about it, prior to Shell’s decision to cease drilling in the Arctic Ocean.

The rain lashes down. A strong south westerly drives it along the Thames, across Jubilee Gardens and against the railway viaduct that separates the Royal Festival Hall from the Shell Centre. The crowd huddles onto the wide pavement beneath the arch. Across the narrow roadway, on the opposite pavement, is the sextet performing the four pieces of the Requiem for Arctic Ice. Beyond the musicians, sightly hidden from view by the crush of damp heads and backs wrapped in anoraks, is Charlotte Church – seated, awaiting her moment.

It’s an eccentric event. To be crammed under a railway arch, avoiding the pouring August rain, listening to the strains of cellos, violins, viola and double bass of the Ligeti Quartet and Kelly Lovelady. Now and again there’s the rumble of a train pulling slowly overhead between Waterloo East and Charing Cross. At frequent intervals the audience’s view of the seated sextet is blocked by a passing single-decker red bus, a white delivery van or a refuse truck. Twice the space of the arch is dominated by the massive yellow hulk of a passing landing craft – emblazoned with the logo London Duck Tours. Despite the distractions and obstructions, the orchestra plays on. Just, as we read on the leaflets that we are handed, like the famed musicians on the deck of the Titanic.

The front row of the audience is bristling with press photographers and TV camera teams – they’re here for Charlotte Church and because of the labours of the Greenpeace press office. Bill Oddie has also come to lend his visible support to the cause. In the distance the head of the Greenpeace Media Team, is chatting with Jon Snow. Channel 4 is clearly creating a package about the event.

The final bars of the fourth of the Requiem pieces ends. There’s a pause and the cameras ready for action as Charlotte Church rises to sing:

This bitter earth

Well, what a fruit it bears

What good is love

Mmm, that no one shares

I’m staring out of the archway. Sheets of rain are moving across the empty lawns of Jubilee Gardens, in the distance is a line of brightly coloured kagools, tourists queuing for the London Eye. Nearer too, the chairs of the fun fair whirly-gig spin through the air, flags fluttering. A policewoman pushes back the press to let a motorbike through the arch. It is so far from the imagined Arctic, yet tears are streaming down my face.

And if my life is like the dust

Ooh, that hides the glow of a rose

What good am I

Heaven only knows

At the opening of the event the artistic director, Mel Evans and campaigner Anna Jones, had spelt out the rationale for the Arctic Requiem. Whilst Shell drills for oil in the Arctic Ocean offshore of Alaska, the team of composers, musicians and facilitators, have been holding, and will hold, daily performances of the four pieces outside the front doors of The Shell Centre. Only on account of the apaulling weather and the size of the crowd has today’s event been moved twenty yards east to the shelter of the railway arch.

Lord, this bitter earth

Yes, can be so cold

Today you’re young

Too soon, you’re old

One of the composers, Chris Garard, has been a stalwart of the Shell Out Sounds group that has used live performances, both outside and inside the auditoria of the South Bank Centre, to draw attention to the fact that Shell sponsored a classical music programme at the QEH. The campaign has been incredibly successful. Within a short few years it seems that the company and the South Bank Center ceased the sponsorship relationship in January 2015. This event today and the Requiem performances over the past three weeks seem like a wonderous evolution of the Shell Out Sounds actions. Here is professional sextet and a world-reknown singer using music as a weapon of protest against the oil industry. But this is not about driving Shell out the South Bank Centre, and other cultural institutions, but about driving them out of the Arctic.

But while a voice within me cries

I’m sure someone may answer my call

And this bitter earth

Ooh, may not, oh, be so bitter after all

After the applause the closes the performance, I head out of the arch into the rain which thankfully has died a little. Around the other side of the Shell Centre, on Belvedere Road the building is covered in scaffolding and looking up I can see that on many of the floors the windows in the smooth wall of Portland Stone, are without glass. Blind eyes in the cold face of rock. The main tower is under reconstruction. This edifice, and the block that lies beyond the railway viaduct behind the Royal Festival Hall, were once parts of the largest office complex in Europe. So large, so up to date, that it had a swimming pool and rifle range for the Shell staff in the basement. Now the entire eastern wing is sold off, turned into luxury appartments in the 1990s. The main tower itself was sold by Shell to Qatari Diar in 2011- the company now only uses a small part of the office space it did in the Sixties. The refurbishment is undoubtedly part of the new owners efforts to attract new tennants.

The Shell Centre was built between 1957 and 1962 on the former riverside wharfs of Lambeth, on land that was effectively publicaly owned by the Port of London Authority. Clad in Portland Stone – the material for the graves of the war dead – its classical Modernism was designed to echo the neighbouring Royal Festival Hall. This latter was also built on former dockland, a public building on public land designed as the epicentre of the Festival of Britain. A People’s Palace. The Shell Centre embodied the sense of the company as a public institution, a national champion, an extension of the civil service. From the tower company staff gazed down upon Parliament and Whitehall across the Thames.

Now the company is slowly vanishing from the public gaze. First, with the closing of Shell Mex House on The Stand and now with the shrinking of its presence at the South Bank. Perhaps in a decade or so the Shell flag will cease to fly over the Shell Centre Tower, just as the Shell logo has ceased to emblazon the South Bank Center Classic Season of music.

The corporation may be retreating from public view, but it is not getting weaker, and it continues to advance into areas of the world that have so far been spared the destruction and upheaval that forever accompanies the exploitation of oil & gas. Shell is currently the largest company, by capitalisation, on the FTSE 100 Index of the London Stock Exchange and yet it is shriking in the public view. The corporation continues to operate as strong as ever before, especially as it proceeds to gobble up BG its other UK based rival, and yet it attempts to do so with increasing invisability.

It was the intention of the Board of Shell that the exploration of the Arctic Chuchki Sea would be treated as a routine affair to which little attention should be paid by investment managers, business journalists, politicians and the general public. The company has utterly failed in this regard. Over the past three years there has been an ever growing focus of attention, in all these spheres, upon the company’s attempts to drill offshore of Alaska. This has been driven by First Nations and environmental groups in Alaska, by activists across the USA, and by organisations such Greenpeace, Shell Out Sounds, Platform and a myriad of others around the world. Together these people have made visible what the company intended to be invisible.

It seems likely that none among the crowd huddled under the railway arch have ever been to Alaska, let alone seen the vast drilling rig that is right now labouring over the horizon of the Arctic Ocean. Yet the strings of the sextet and the voice of the singer performed a great function of art – they rendered the invisible visible.

After Thought.

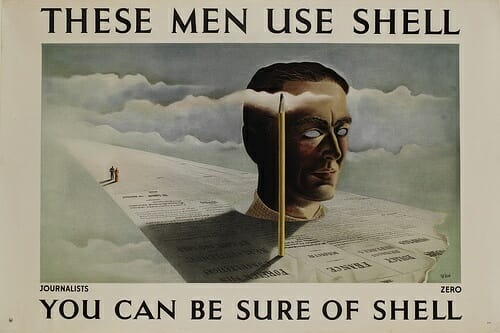

From the 1920s Shell employed some of the most renowned British artists to help sell its products. Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland, Vanessa Bell, and several others were commissioned to design posters for Shell Mex-BP motor spirit, or petrol. With the iconic strap line ‘You can be sure of Shell’ their work included Hans Schleger’s 1938 ‘lorry bill’ – ‘These Men Use Shell – journalists – You can be sure of Shell’

The Shell Guides were launched in 1934, edited by John Betjeman and subsequently John Piper. They were popular companions to the counties of England encouraging tourism by car. The same year film makers such as John Grierson began to be employed to shoot short movies documenting the work of the company.

In 1985, after sixty years, this phase came to a close – the Shell Film Unit was shutdown and the Shell Guides ceased to be published. In their place the corporation began to sponsor the arts – not financing artists to create art about the company, but rather using the company’s capital to finance public galleries to show art to the public. The company, using the vehicle of the national institutions to build its reputation with key ‘special publics’ and thereby, bolstering its ‘license to operate’. Now that phase seems to be closing as the battle against oil industry sponsorship of the arts is steadily being won – as is brilliantly documented in Mel Evan’s book ‘Artwash’.

It is intriguing that as the Shell logo disappears from the brochures of the South Bank and other cultural institutions, and as the company becomes more invisible to the public, that artists are increasingly creating work that portrays and reveals the corporation once again – from Greenpeace’s ‘Requiem for Arctic Ice’, to Platform’s ‘Living Memorial to Ken Saro-Wiwa’ by Sokari Douglas Camp, and Theatergroep Hollandia’s production of ‘Voices’ by Tom Blokdijk (based on writings of Pasolini and the speeches of Cor Herkstroter, former CEO Royal Dutch Shell). This time these artists are not on Shell’s payroll, and the wider public, journalists, investment managers and even politicians, are becoming increasingly less sure of Shell.