A guest blog by Hamza Hamouchene, who is currently at Platform researching UK’s energy interests in Algeria.

With the production of North Sea gas dwindling dramatically, developing Algeria as a major natural gas exporter has become an economic and strategic imperative for the EU. The country features heavily in both EU and UK energy policies and has been identified as a priority market under the UK Department of Energy and Climate Change’s (DECC) international energy security policy. But does the political drive to securing these exports mean that western politicians and companies will ignore a whole host of human rights abuses and strengthen the hand of one of the region’s most repressive regimes?

Algeria is the largest country in Africa and very rich in natural resources. It’s the 3rd biggest producer of oil in Africa after Nigeria and Angola, and also one of the top natural gas producers. It’s the third-largest supplier of natural gas to the European Union (after Russia and Norway), providing some 10-20 percent of the EU’s consumption, and could be meeting about 10% of the UK gas demand in coming years via the newly-expanded Isle of Grain LNG terminal in Kent according to a recent UK Trade and Investment Defence Security Organisation briefing. It also holds vast untapped “unconventional” shale gas resources which according to the US department of energy makes Algeria the third largest recoverable shale gas reserves holder after China and Argentina. Shell and ExxonMobil have already held talks with the national oil company Sonatrach about shale gas extraction, despite the enormous environmental impact it could have on the Sahara.

The tragic attack on the BP’s Amenas gas plant in south-eastern Algeria in January 2013 resulted in the death of 39 foreign hostages (including 6 Britons and 1 UK resident) and the killing of 32 terrorists. Algeria’s role in the global “war on terror” was strengthened in the aftermath, with Western interests deepening the collusion with the authoritarian, repressive regime and thus contributing to its longevity.

Despite criticizing the way that Algiers handled the crisis, several Western leaders still voiced strong support and vowed to increase security cooperation to eradicate terrorism. The UK was no exception, with Prime Minster David Cameron pledging a global response to what he considered an “existential” and “global threat” to “our interests and way of life”, while making a historic trip to Algeria – the first post-independence visit by a serving Prime Minister.

Phrases such as “fighting terrorism”, “security cooperation” and “our interests” have often been euphemisms for “militarisation” and “lucrative economic deals”. The language is part of a diplomatic agenda of promoting British interests and influence in Algeria while disregarding despotism and human rights abuses. This was the same approach that characterised UK relations with ‘friendly’ dictators like Ben Ali of Tunisia and Mubarak of Egypt that were swept away by the Arab uprisings.

Algeria has escaped from an “Arab Spring”-style uprising mainly because of the aborted “democratic transition” of 1988-1991 that ended up in a traumatic decade-long civil war. The country however possesses all the elements of a powder-keg: authoritarianism, inegalitarian development, high unemployment, poverty, endemic corruption and nepotism, stifled political expression, human rights abuses, a frustrated educated youth without opportunity and a parasitic ruling elite. Outside of the international media spotlight in 2010/11, the country saw an unprecedented number of demonstrations, strikes, occupations, and clashes with the police. In 2010 alone, the authorities counted 11,500 riots, public demonstrations and gatherings across the country. More recently there has been growing discontent and mobilisation from the unemployed movement (Le Comité national pour la défense des droits des chômeurs, CNDDC, National Committee for the Defence of Unemployed Rights), especially in the oil-rich Sahara, a region that provides the bulk of Algeria’s resources and income but that suffers from long–term political and cultural marginalisation.

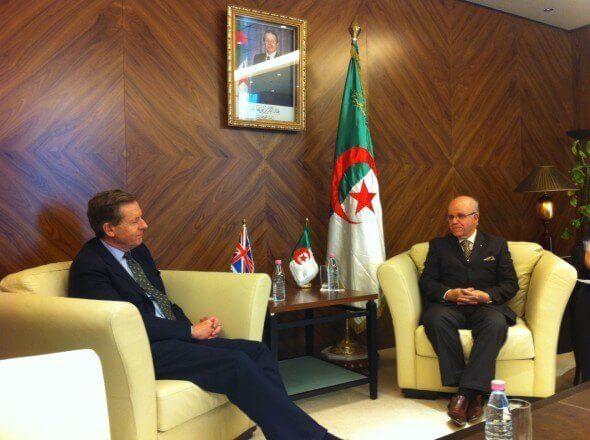

British investment is growing in Algeria and is deemed important enough to have justified the appointment last November of a special UK trade envoy for Algeria, Lord Risby, and the creation of a dedicated British-Algerian business council, ABBC, lead by Lady Olga Maitland. Lord Risby has already been involved in promoting energy deals with repressive regimes, taking part in a trade mission to Azerbaijan in 2012. Lady Olga is also the president and founder of the Defence and Security Forum, a think-tank in the defence sector.

Algeria was listed as a ‘priority market’ by UK Trade and Investment Defence and Security Organisation (UKTI DSO) in 2010/11, emphasizing how the UK has been keen to pursue arms sales to Algeria in recent years despite damning reports by several NGOs such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and UN Watch putting Algeria as one of the worst offenders in the region when it comes to human rights.

David Cameron’s announcement of strengthening the military partnership with Algeria is part of the UK ‘energy diplomacy’ aimed at securing access to strategic resources in North Africa and safeguarding their supply. However, promoting such an agenda while turning a blind eye to Algeria’s human rights abuses is morally unacceptable, must be challenged and should be subjected to greater public and parliamentary scrutiny.