Mika Minio-Paluello, Anna Galkina and James Marriott travelled in North America as part of a tour over September and October to promote The Oil Road – Journeys from the Caspian to the City of London. The ninth of a series of blogs on the journey comes from Pennsylvania…

Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania

Long hours under rough blankets. The cotton sheets tender against the skin. The lungs breathing. The chest rising and falling. The sound of incessant feet along the linoleum corridors. The rumble of cars and trams on North River Street. The thudding boat engines on the Susquehanna river. The laughing calls of the crows in the trees of the River Common. It is said that Morgan James – my partner Jane Trowell’s great uncle – lay in a hospital bed in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania for a full six months after the accident. But much of this story is unclear.

Morgan was born in 1902 at Taibach on the edge of the conurbation of Port Talbot in South Wales. Number 3, Inkerman Row East, where he grew up with his three brothers and four sisters, was ‘Up the side’ – up on the side of the mountain, the Mynydd Margam. The slopes of rough pasture and gorse looked out over Margam Sands, Swansea Bay and the Severn Sea beyond. The town of Lynmouth far off in Devon was visible when the sun shone and the weather was clear. Like the majority of men in the area, Morgan went to work in the coalmines that riddled the mountain, burrowed under the town and tunneled beneath the seabed.

The decade after the First World War saw a sharp decline in global demand for coal, in particular for the Steam Coal that was hacked out of the Welsh mountains. This particular quality of anthracite was ideally suited to the furnaces of marine engines, for cargo ships and liners, battle cruisers and tramp steamers. But in many of these vessels, coal was being replaced by oil, refined in new plants such as that of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company at Llandarcy, five miles west of Taibach. From the end of 1920 there was an acute slump in the coalfields that lasted fifteen years and saw up to a third of the male population unemployed, wage freezes and appalling poverty.

It may have been the experience of seven bitter years and the lack of any future prospects that encouraged Morgan to leave, but nothing is clear. His brother Elfed managed to remain employed, working in the Newlands pit whose shafts ran out under the sea. There was a family rumour that Morgan was blacklisted by the mine owners for his part in the turbulence as the unions struggled to defend jobs and wider rights such as access to health care. Certainly he’d been an active organiser in the seven-month-long miners’ strike of 1926, which was the central part of the General Strike. Perhaps like many he felt bitterly disillusioned in the years that followed.

Whatever the cause, together with his friend Thomas Howell David, he took the train to Southampton and then sailed for New York on the 28th March 1928. Travelling 3rd Class in the MV Olympic Star, sister ship to the Titanic, they arrived in the America of the Roaring Twenties. Morgan and Thomas Howell journeyed into the Appalachians and the Wyoming coalfields of Pennsylvania. The name Wyoming derived from the Native American Munsee word meaning ‘at the big river flat’. Here the Susquehanna carved a valley through gently rolling mountains, reminiscent of the shape of hills behind Taibach, only clothed in thick forests.

It seems that Morgan and Thomas Howell found employment within the next few months – certainly by 1st November 1928 they had obtained certificates proving that each was a ‘Qualified Miner’. A month later both of them filed ‘A Declaration of Intention’ to become a citizen of the United States. This was surely the dream of a new life as they worked the rock-face in the narrow seams beneath the river and the mountains. It was exactly a year before the Wall Street Crash.

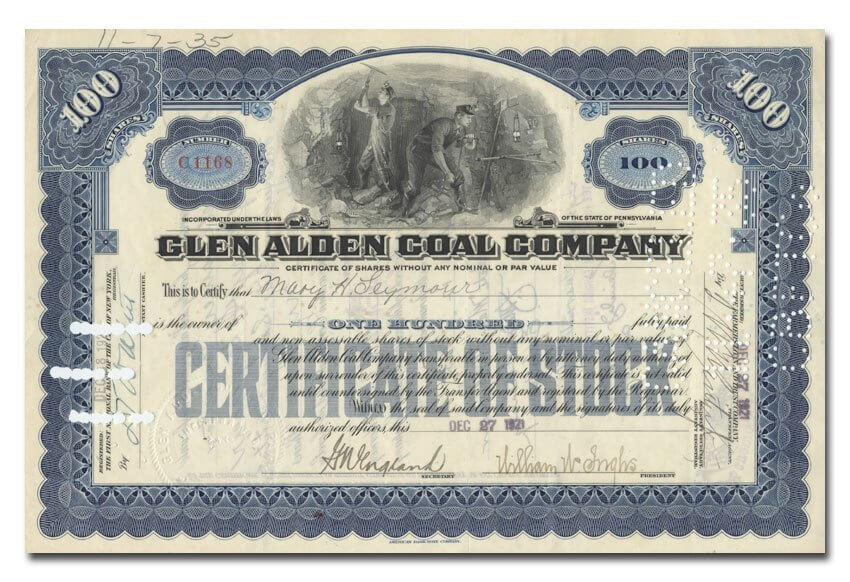

The impact of the Depression on the mining communities of Pennsylvania was severe. Over several months many of the collieries around Wilkes-Barre worked only a few days a week, while others shut down entirely. To the many miners from Wales it must have felt painfully reminiscent of the world that they’d left behind. By 1930 Thomas Howell had left the coalfields to live with his aunt in Granite City near St Louis, Missouri, finding employment in a tin plate works. Morgan remained in the Wyoming valley, labouring in the Buttonwood No 20 Mine for the Glen Alden Coal Company, an employee of President & General Manager Shelby D. Dimmick. Along with the other office staff, Mr Dimmick worked in the company headquarters on South River Street. This massive white Neo-Classical block towered above the bridge spanning the river at Wilkes-Barre, the gateway to the town.

The winding gear, or ‘breaker’, at the head of the Buttonwood mineshaft was only a few hundred yards from the cluster of streets that made up Hanover Township where Morgan lived. Like all the other settlements in the Wyoming it was a workers’ village populated by immigrants from countries such as Poland, Slovakia and Wales. There were three Welsh Baptist chapels and two Welsh Presbyterian chapels in the area of Wilkes-Barre – voices singing in Welsh in the valley of the Susquehanna.

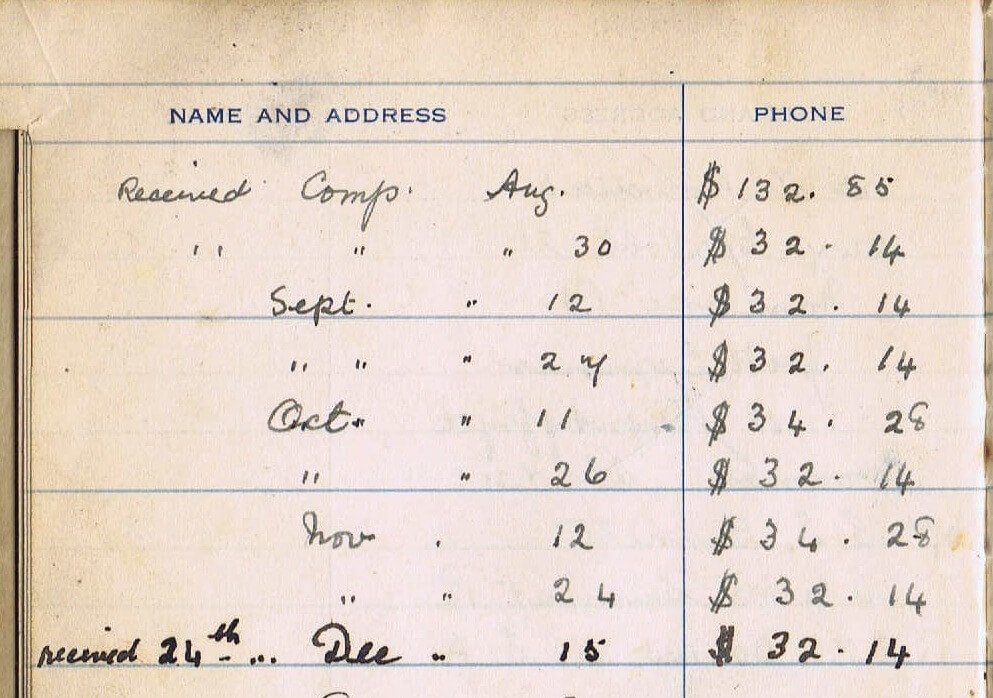

The list of dates and sums in dollars runs, ink pen in a neat hand, over four pages of a slim black-bound notebook. It belonged to Morgan’s mother Mary, or ‘Mam’, James. It is the record of payments that were received in compensation for an accident, and as the sums are in dollars in a South Wales book, then they must relate to an injury that had taken place in the US, with the payouts coming from an American company. On the following pages are sixty addresses, written in the same hand, over half of them are for places in America, 19 are from Wilkes-Barre.

Mam James is the great-grandmother of my partner. We have had this notebook in our house for several years and have puzzled over it many times. Armed with a few shreds of stories, I am finally following the trail of Morgan, picking up the lead that the notebook provides, travelling by bus from Buffalo and Rochester, through Scranton, to this northeast corner of Pennsylvania. Wilkes-Barre, which went into a long decline after the mines closed in the late1950s, is hard to reach for the foreign traveller. I am determined to make it to the archive of the Luzerne County Historical Society before Saturday closing time.

Amanda Fontenova, the neat archivist, takes the arrival of a foreigner asking for evidence of a relative in her stride. I’m efficiently instructed to sign in and take a place at one of the desks. She brings volumes of the Wilkes-Barre Record Almanac and I start the search for Morgan. I am not alone in this set of small rooms cluttered with artifacts, pictures, filing cabinets and shelves of books. Others are here sifting through the remains of an industry that has lain in ruins for half a century.

I read the Almanac and its record of ‘Mining Affairs’ for each year. It vividly describes the 1931 convention of the United Mine Workers of America – the UMWA – in nearby Scranton:

proceedings were retarded by bitter antagonism between administration and anti-administration forces … Two of the sessions were broken up by riots. Tear gas bombs were necessary at one session to quell the disturbance. … Dr A. M. Northrup, State secretary of labor, narrowly escaped being trampled upon when a mob stampeded the speakers platform at the opening session

So intense was the anger of union members at the collusion between their leadership and mine owners, such as Shelby Dimmick, that the UMWA split in July 1932:

a new union, the United Anthracite Miners of Pennsylvania, was organised, and war declared on the United Mine Workers of America and the anthracite operators’

The Almanac records that 18 months later, in 1934:

On January 13 the new union called a general strike and disorder ensued. There were riots, dynamitings, shootings and assaults. Numerous persons were injured and went to hospitals. Jail sentences were imposed. Property was damaged.

Two men in their twenties enter from the street in T-shirts, ragged jeans and baseball caps: “We’re looking into a mining accident” one declares to the archivist. She replies in a matter-of-fact tone: “When was the person killed? After the1920s there was a cut back in the keeping of records, and they cease to list many of the deaths”. “Slave labor”, says the guy in the cap. “He was killed in 1952 on Christmas Day. Happy Christmas Grandad!” The archivist rises, walks to a nearby stack, and shuffles through a wooden drawer of well-thumbed index cards. I’m filled with the sense that all of us in these rooms are quietly searching through the shelves and filing cabinets for some evidence of those who gave their lives in a great war: the mighty firestorm of the hewing of carbon from the mountains.

Two men in their twenties enter from the street in T-shirts, ragged jeans and baseball caps: “We’re looking into a mining accident” one declares to the archivist. She replies in a matter-of-fact tone: “When was the person killed? After the1920s there was a cut back in the keeping of records, and they cease to list many of the deaths”. “Slave labor”, says the guy in the cap. “He was killed in 1952 on Christmas Day. Happy Christmas Grandad!” The archivist rises, walks to a nearby stack, and shuffles through a wooden drawer of well-thumbed index cards. I’m filled with the sense that all of us in these rooms are quietly searching through the shelves and filing cabinets for some evidence of those who gave their lives in a great war: the mighty firestorm of the hewing of carbon from the mountains.

I have begun to lose hope of finding any evidence of Morgan, one injured miner among thousands, when suddenly he appears, backlit on microfiche.

Wilkes-Barre Record – Thursday May 24th 1934

MINER KILLED IN ROCK FALL

ANOTHER HURT IN SIMILAR ACCIDENT REPORTED IN SERIOUS CONDITION

Morgan James, 32, of 6 Phillips Street, Hanover Township, suffered a fractured pelvis and probable broken back yesterday when caught in a rock fall in No 20 Glen Alden Coal Company. His condition was reported as serious in General Hospital last night.

It begins to fit together. E-mailing with relatives in Wales, I find that Morgan’s mother and his elder brother Ivor boarded a ship in Southampton on 13th June, crossed the Atlantic and came to the hospital bedside in Wilkes-Barre. At some point it must have become clear that Morgan would survive, perhaps in July – the very same month that Shelby Dimmick died suddenly of an infection. How long the three members of the James family stayed in the town is not clear, but in early December they took the MV Olympic Star from New York back to Southampton. Morgan had obtained his American citizenship – intent it would seem on settling in the US. But he was carried home on a stretcher, an industrial invalid returning on the same ship to live with his parents in South Wales. On arriving at Taibach, gifts from the States were given out – for the grand-daughters organza dresses with bows and matching white shoes.

In the garden below Inkerman Row East in Port Talbot there were two sheds. The lower one, built of brick, housed a fret saw, a treadle and a workbench with tools. Morgan made wooden toys, bags out of leather and flat, painted, policemen, each one with his arms outstretched holding an ashtray. His mother kept the notebook of the compensation that arrived in dollars, every two weeks for five years, until the outbreak of the Second World War in October 1939. Eventually Morgan was able to walk, and during the war got work with the General Post Office driving a van around the district.

By the late 1940’s Morgan was driving for the construction company, Wimpey, firstly at The Steel Company of Wales plant in Port Talbot, next at the Shell refinery in Ellesmere Port, where workers’ housing was being built, and finally around the Distillers plastics factory that started in Barry. The post-war Labour government had opened a whole new industrial era for South Wales. The coal, gas, electricity and water industries were taken into public ownership, the Steel Company of Wales was established and private companies, such as Distillers, were encouraged to invest. Wages rose, unemployment almost vanished, and the National Health Service was born. For many it felt like the dream struggled for in the 1920s and 30s, was being realised.

Whilst working for Wimpey, Morgan met Flo. Late in life they were married, and lived in Port Talbot before retiring to her home town, Barry. By this time he was suffering from pneumoconiosis, or ‘black lung’. Two cylinders of oxygen, provided to his home by the NHS, kept him breathing. It was forty-one years since he worked Buttonwood mine, tunnelling under the Appalachian mountains, but it was the coal that eventually killed him in 1975. The geology of Pennsylvania was shipped back across the Atlantic in his lungs and cremated with him in South Wales.

Thanks to Llewela Gibbons, Amanda Fontenova, Dr Cliff David, Michael Phelps (West Glamorgan Archive Service), Rory Gibbons, Susan Griffiths, and Jane Trowell.